Kristan Stacey: We Are All Treaty People

This course provided me an outlet to reflect deep within myself about how I relate to Indigenous people and their rich histories in Canada. I have learned a lot about myself and who I am in connection to Indigenous people, histories, and land in Canada. In this reflective paper and creative collage piece, I will examine my personal journey of examining Indigenous settler relations in Canada.

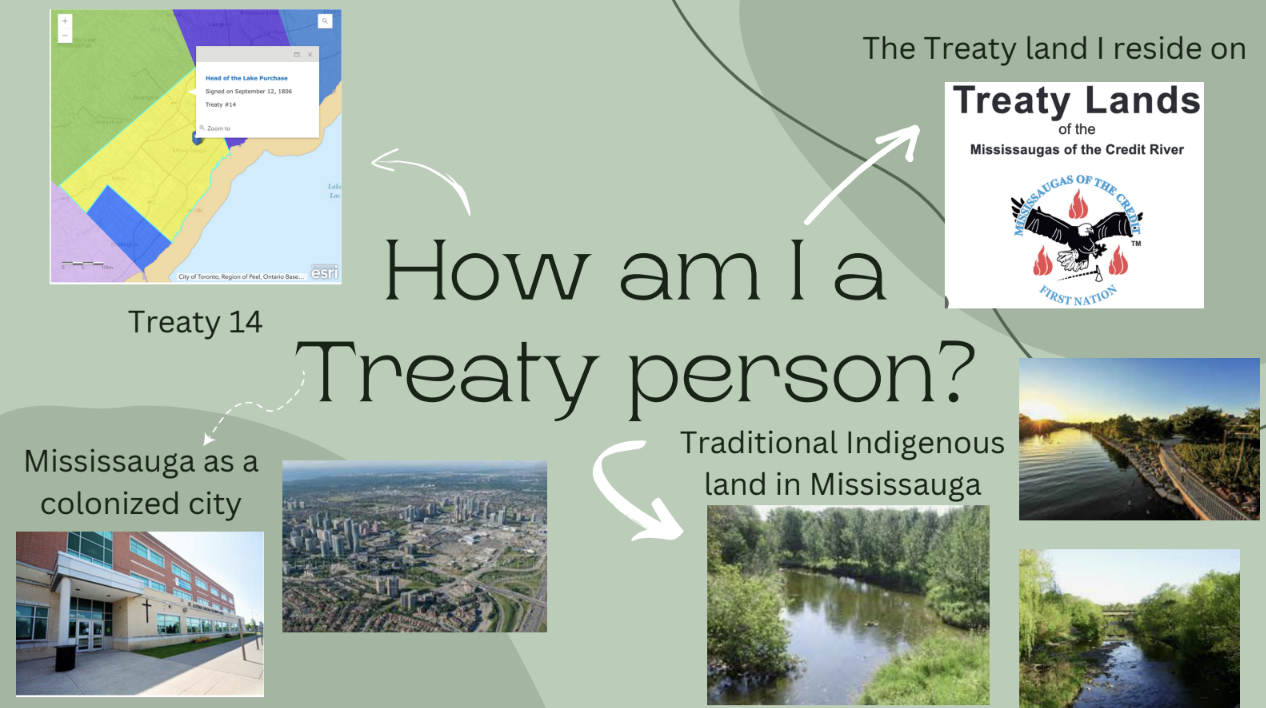

To begin, I would like to highlight my positionality and how this relates to Indigenous people. This course has provided me with the knowledge and vocabulary I need to understand that, as someone with European heritage, I am a settler in Canada (Christensen, January 2023, Intro, GPHY 351 W23 Lecture). Both sides of my family come from European descent, meaning that we have, and currently, reside on stolen Indigenous land. I am also able to identify that the communities I am in are on Indigenous land. My hometown of Mississauga, Ontario is on traditional territory and treaty lands of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nations, Anishinaabe lands, Haudenosaunee lands, and the Huron-Wendat lands. I have also come to learn that Queen’s University is also on stolen Indigenous land, specifically, Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee traditional lands. This course has shown me the importance of acknowledging traditional lands as Indigenous peoples have ancestral and spiritual ties to the lands as their ancestors lived on this land prior to colonization and settlement (Christensen, January 2023, Geography… Indigeneity, GPHY 351 W23 Lecture). These lands remain under the power of settler governments, but recognizing and acknowledging the land is a first step towards decolonizing land in Canada.

We are all treaty people

This course has also challenged me to think about how I am a Treaty person and how I have benefitted from the numerous Treaties between settlers and Indigenous people that have occurred throughout history. I learned that my hometown is part of Treaty 14: Head of the Lake Purchase (Government of Ontario, 2018). Treaty 14 affirmed the importance of the fisheries at Twelve Mile Creek, Sixteen Mile Creek, Etobicoke Creek, and the Credit River for the livelihoods of the Mississauga Indigenous people. These are all rivers that I am familiar with in Mississauga, and I often find myself by these bodies of water in the summertime. Learning about this treaty has shown me that this Treaty meant that the Indigenous groups of this area would unknowingly cede their rights to their ancestral lands (Wilkinson, 2020). I have directly benefitted from this Treaty as my home, grade schools, and my employment with the City of Mississauga are all on ancestral Indigenous land. As discussed in class, the erasure of Indigenous history and culture occurred with Treaties, allowing for settlers to control and use the land (Christensen, January 2023, Spatial Erasure, GPHY 351 W23 Lecture). I feel as though it is important for me, and others of settler descent, to recognize that we have directly benefitted from dispossession of Indigenous people due to colonialism. As we discussed in class, ignoring the history of traditional lands leads to narratives that undermine Indigenous claims and ways of life (Christensen, January 2023, Spatial Erasure, GPHY 351 W23 Lecture). Learning the true history of the lands I live on has been a key piece of my personal journey.

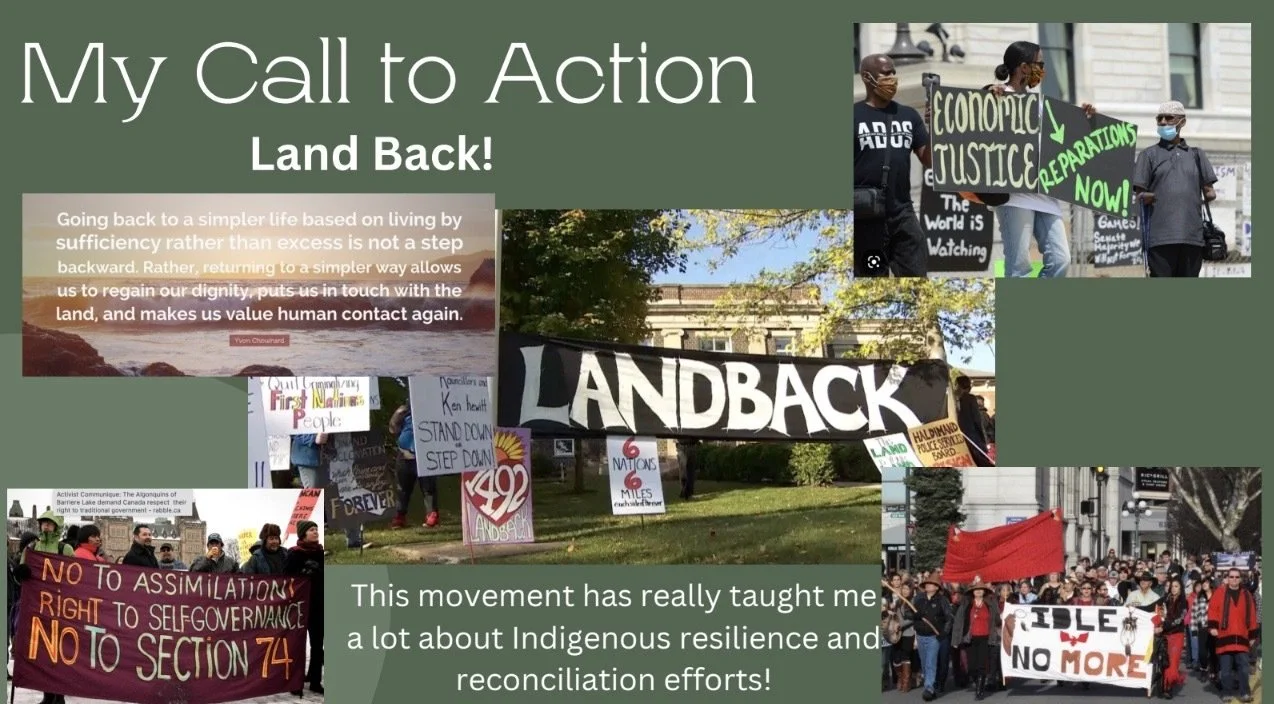

Land Back

I believe that the “Land Back” movement is an essential Call to Action towards reconciliation and decolonization in Canada. The movement for decolonization in Canada is not complete without land restitution for Indigenous people. Land Back requires that settlers work to repair the harm that colonialism has done and continues to inflict on Indigenous People by returning control over their ancestral lands and territories back to its stewards, allowing them to begin restoring their connection to the land in meaningful ways (Belfi et al., 2021). Transferring this power and wealth back to Indigenous People in Canada, which includes water, natural resources, and infrastructure on the land, directly supports Indigenous sovereignty. The Land Back movement is essential for securing self-determination, environmental sustainability, and economic justice for Indigenous People in Canada (Belfi et al., 2021).

The goal of Land Back is for Indigenous People to have self-governance. To achieve this, Canada must understand the historical context of Indigenous peoples and the dispossession from their ancestral lands that occurred due to colonization (Christensen, March 2023, Land Back Lecture 2, GPHY 351 W23 Lecture).

This will help to illuminate the negative aspects of current land management strategies, which will highlight why the Indigenous led Land Back movement is necessary. The Land Back movement does not ask current Canadian residents to vacate their homes, rather, the movement seeks to reinstate Indigenous governance for sustainable public lands (Christensen, March 2023, Land Back Lecture 2, GPHY 351 W23 Lecture). A decolonial lens of land management is necessary to avoid reproducing the destruction of land brought about by colonization (Belfi, 2021). The Land Back movement explores potential paths toward equitable and just systems of land management that honor Indigenous rights and responsibilities to the land. This includes the inclusion of Indigenous systems of governance and stewardship and creating meaningful relationships between the Canadian government and Indigenous People for the future (David Suzuki Foundation, 2021).

Calls to Action

There are many ways that I can support this Call to Action in my personal life. Firstly, I can continue to learn about the movement and educate those around me. Educating myself and others about the history of Indigenous peoples in Canada, including the ongoing impacts that colonialism has on Indigenous people is essential for reconciliation efforts. I can also listen to Indigenous voices and stories and amplify them in society. This includes amplifying Indigenous perspectives, and the unique experiences of Indigenous people and their communities. I can do this by attending Indigenous-led events and protests, following Indigenous activists and organizations on social media, as well as joining activism efforts on campus. Advocating for policy change is also essential for reconciliation efforts through the Land Back movement. Advocating for policy changes at the local, provincial, and federal levels will help ensure that policies and monetary funds support Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination in Canada. This could include advocating for the recognition of Indigenous land rights and the implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (David Suzuki Foundation, 2021). Building relationships with Indigenous people through acknowledging their sovereignty and self-determination, as well as their histories in Canada is essential for decolonizing land in Canada. In summary, I can support the Land Back movement in my personal life by educating myself and others, listening and amplifying Indigenous voices, advocating for policy change, and building relationships with Indigenous people.